Staff Spotlight: Introducing Director of Research Development Darine Zaatari (Take Two!)

It has been more than a year since Darine Zaatari stepped into her new role as director of research development in the Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences (ICS). Yet her April 2021 start date occurred when much of the UCI campus was remote because of the COVID-19 pandemic, so she didn’t get the typical Donald Bren Hall (DBH) meet-and-greet walkthrough. You might only know her through the email sent from ICS Dean Marios Papaefthymiou, which read in part: “Dr. Zaatari comes to our School with several years of experience in managing large-scale projects in academia and industry. We look forward to her contributions in expanding the scope and visibility of our research enterprise.” So, who is Dr. Zaatari, what exactly does she do, and why might it be hard to catch her in her DBH 6054 office this month?

What’s your backstory, and how did you end up at Rutgers, where you earned your Ph.D.?

I grew up in a coastal city by the Mediterranean called Sidon, where I spent all of my childhood until I got into grad school. When I was doing my master’s at The American University of Beirut (AUB), I was very interested in the brain and the ancient debate of whether it’s a blank slate and we acquire knowledge and skills, or whether we come already equipped. While there, I came across a cognitive evolutionary approach to understanding the brain and how our brains are wired, so I was curious about applying evolutionary theory to explaining animal behavior. I signed up for this [Field Studies in the Evolution of Animal Behavior] course in Montana at the Flathead Lake Biological Station to learn a little bit more about animal behavior and evolutionary theory. So, there I was, coming from a little town on the Mediterranean coast, hopping onto a very, very tiny plane and going to Montana to live in a cabin!

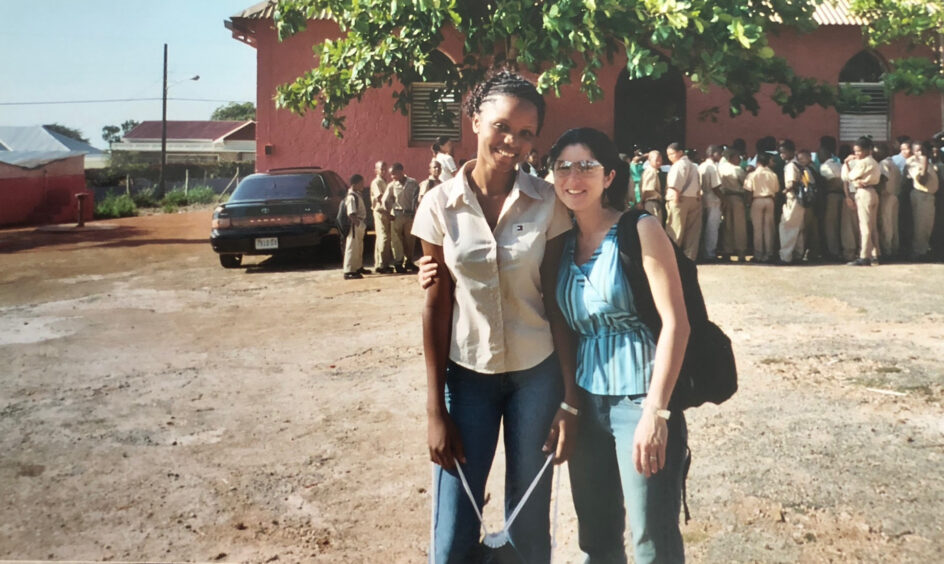

It went really well, and I enjoyed understanding animal behavior generally, but I was more of a people person, so eventually I wanted to use evolutionary theory to better understand human behavior. Fast forward to grad school at Rutgers, which had a program in physical and biological anthropology, and I went to school there to focus on understanding cooperative behavior and punitive behavior using evolutionary theory. In particular, I applied it within the context of punitive and cooperative behavior using the methods of game theory. So it’s basically getting a bunch of people in certain contexts, giving them an opportunity to cooperate or defect using an economic game to play, observing their behavior, and then using biological traits to see how those tools can help us predict and explain some behavioral tendencies. I did field work using these methods in Jamaica and Lebanon as well, so that’s the quick and dirty version of my background.

How did that lead to where you are now?

After I was done with grad school, I had my first child, and then there was the 2008 financial crash, so the economy was horrible. I didn’t want to stay in academia, and I was trying to explore different pathways, but the timing was really bad, given the economy. I became a field interviewer for a while, collecting data for social science research, but I was more focused on being a mom, and I wasn’t working full time.

Later I worked at Google for a little bit, doing user research. As an evolutionary anthropologist, I enjoyed user research and I’ve always connected it to statistics and the tech side of things. At the time, Google wanted to create this product called the Ara phone, which was a smartphone that you could customize with the actual hardware, based on your needs — like adding onto a Lego base. So you could add a gigantic camera if you were obsessed with taking pictures. My job was to solicit people’s input from around the world by giving them homework every week, using different videos or drawings or surveys, on topics such as how big the phone should be and what it should look like. It was a great idea, but we never pushed through to get there, and at some point, I felt I was ready for a change.

I spent a good chunk of my career working for the NORC research center at the University of Chicago, which is the private equivalence of the Census Bureau. I was mostly involved in trying to optimize field operations, looking for quantitative strategies to increase data collection efficiency, so I did a lot of project management work. It’s in Chicago and I’m here [in California], so I worked remotely, and eventually I decided I wanted to make a more local connection and to connect back with academia, so this [ICS] position was a great opportunity.

And what exactly is your role in ICS?

I want to be the go-to person for all research-related matters at ICS. This is my goal, so I spent a good chunk of my time when I first came here getting to know the faculty. There are over 100 faculty and they have many different specialties. There are still people I’ve not met, but for me to do my job properly, I needed to understand our strengths and expertise. Knowing the faculty allows me to identify the opportunities that we should pursue, so I can then encourage them to go after these things, letting them know that they won’t be flying solo — they’re going to have my support and I will get them through it.

The primary part of my job is to support faculty to put together big proposals — which tend to be very high maintenance and require a lot of effort. As you know, faculty have a lot of things going on, so a big part of it is project management, because you’re bringing a product from start to end, and there are many details, partners and stakeholders throughout. At the same time, I’m trying to fill a gap for junior faculty who don’t have as much experience in applying for funding. So I created a website with research development resources, including a lot of the boilerplate text that’s often needed. My focus was NSF and I still need to do the NIH boilerplate, but it lets faculty just grab text from a template to lessen the burden and help them turn around proposals a little faster.

What’s your schedule, and how does your work fit in with the Contracts and Grants team?

I’m on a hybrid schedule, and honestly, for me to accommodate the demands of my job, it’s far easier for me to be at home, because my work is not a nine-to-five job. I’m working with faculty who work nights or are in different time zones, so having the flexibility of the hybrid schedule increases my productivity. Currently, I have two projects that I’m working on, two proposals, both due in May.

I work with [ICS Contract and Grant Manager] Mark Gardiner’s team. They have their processes in place. When I take on a project, I always reach out to whomever is the assigned person on our team and work out the division of responsibilities. I try to help out when needed and reach out to faculty and other partners. It’s been wonderful! I really enjoy working with them and we’ve been successful in our interactions.

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I don’t have spare time! I don’t really have a life of my own, so to speak. In addition to work, I have three children, all in competitive swimming — the most time-consuming sport to ever exist in the world! If I’m not working, I’m probably driving to or from the pool or volunteering at swim meets. I am also a certified USA swimming official, and I spend some of my weekends officiating meets. A good part of my spare time is spent taking care of my kids and their activities. What else do I like to do? I also like to go on walks and listen to audio books or podcasts, depending on my mood. I’m a news junkie, and as for books, I go through different stages, but now I’m learning a little bit more about the country’s history, as told by a new generation of writers. I’m listening to Project 1619 right now.

What do you like best about your work?

What gives me the most rewarding feeling is when I see that something I’ve done has benefited the faculty and I feel that it has made a difference, even if it’s just providing a resource they wanted. So that’s the best part — seeing the positive outcome of something I did. I really want the faculty to feel comfortable reaching out to me and asking for help.

— Shani Murray