Security Vulnerability in Self-Driving Cars Unveils Achilles’ Heel of Sensor Fusion

At the recent Usenix Security Symposium, Computer Science Professor Qi Alfred Chen and his research team presented a first-of-its-kind study revealing a “take-over vulnerability” in self-driving car systems that could result in serious accidents.

Today, more than 40 auto brands and other tech heavyweights are investing in self-driving car technology, and a few of them — including Google Waymo, Baidu Apollo Go and Pony.ai — have been running self-driving services, such as taxi and package delivery services, on public roads for months now. The COVID-19 pandemic has only further increased the growing demand for this technology. According to a recent Market Watch article, “autonomous vehicles have come in quite handy while battling against COVID-19, given the rising need to transport food and essential medical supplies to medical professionals and also those living in infected locations.”

However, with this increased use of self-driving cars comes a need to better understand the potential security threats. Recognizing this, researchers from UCI’s Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences (ICS) have conducted a study of high-level self-driving car systems and discovered a “take-over vulnerability” that, if exploited, could result in serious accidents. The researchers — computer science Ph.D. student Junjie Shen, master’s student Jun Yeon Won, undergraduate student Zeyuan Chen, and Assistant Professor of Computer Science Qi Alfred Chen — presented their findings on Aug. 13 at the 29th Usenix Security Symposium (Security ’20).

Their paper, “Drift with Devil: Security of Multi-Sensor Fusion based Localization in High-Level Autonomous Driving under GPS Spoofing,” is a first-of-its-kind study of certain security vulnerabilities in self-driving car systems.

Take-Over Vulnerability

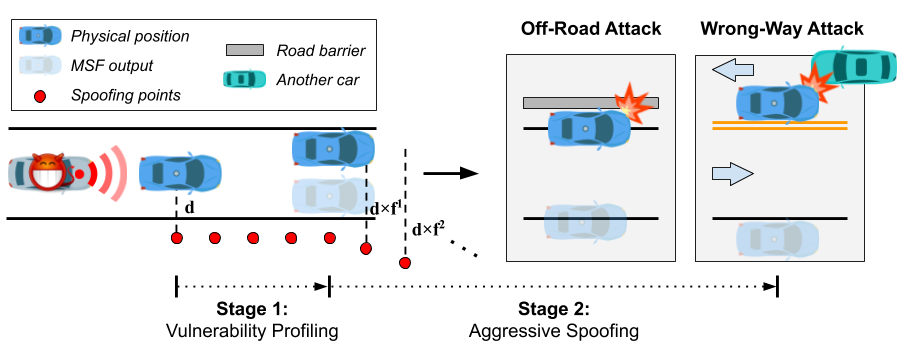

Today’s high-level (level-4) self-driving car systems predominantly rely on sensor fusion algorithms that combine sensor inputs from GPS, LiDAR and IMU to achieve robust localization. “We discovered that the most widely adopted sensor fusion algorithms exhibit a take-over vulnerability to GPS spoofing attacks,” says Shen. “By exploiting this vulnerability, the attacker can use existing GPS spoofing techniques to quickly introduce a lateral deviation as large as 10 meters in the localization estimation, eventually causing the victim self-driving car to drive off or on the wrong side of the road.” The team then designed a novel attack, dubbed FusionRipper, to effectively explore this vulnerability.

After evaluating six real-world sensor traces, they found that FusionRipper could achieve at least 97% and 91.3% success rates in all traces for off-road and wrong-way attacks, respectively. They also recorded attack demos in production-grade simulators to concretely illustrate the end-to-end safety impact. In one attack demo, you can see how FusionRipper forces the vehicle to the right, causing it to run into a traffic sign. In a second attack demo, FusionRipper steers the vehicle to the left, where it drives into a barrier.

Fundamental solutions that prevent GPS spoofing are not likely to happen in the short term. “The only actionable defense strategy we have identified so far is to detect the attack attempts and perform an emergency stop,” explains Shen. “Although this can still cause a denial-of-service of the self-driving operation, it can at least prevent or mitigate further safety damages such as hitting road curbs, falling down the highway cliff, or being hit by other vehicles that fail to yield, especially when the self-driving car is going the wrong way.”

Potential False Sense of Security

Unfortunately, trust in sensor fusion algorithms might provide a false sense of security. “A big contribution of this work is to raise the awareness of the security of sensor-fusion-based localization for self-driving cars,” says Shen. Although prior research has viewed sensor fusion as a promising defense to GPS spoofing, Shen and his colleagues show that this is not necessarily true. “As long as the GPS spoofing is performed strategically, attackers can just tailgate a self-driving car for two minutes and will almost always (97% chance) find an opportunity to break sensor fusion, causing the victim self-driving car to drive off the road or in the wrong direction.”

Professor Chen agrees. “The main real-world impact of this paper is to point out that sensor fusion is not a panacea for self-driving car security,” he says. “As we show in our research, it can increase the robustness in general, but can still fail under more strategic attacks.” To ensure self-driving car developers are aware of this fault, the team contacted 29 companies developing or testing level-4 self-driving cars. Thus far, 17 of the 29 companies have responded and said they are investigating the issue — and one of the 17 is already working on a fix.

“The good news is that we heard a limited number of self-driving car companies have already deployed some GPS spoofing mitigations in their self-driving cars,” says Shen. These mitigations would raise the difficulty of performing successful attacks, but they do not fundamentally solve the problem. “Moving forward, significant efforts are required for both us and the self-driving car companies to explore how to practically address this problem without affecting normal self-driving operations,” he says. “We are currently actively seeking collaboration with those self-driving car companies to work on the defense.”

— Shani Murray